Social care practice is framed within many relationships and continuums. These include care/control, process/outcome, risk/resilience, behavioural/psychoanalytical and keeping children safe/assisting children to reach their full potential, to name but a few. For practitioners it can be enticing to follow approaches such as case management/instrumental/systems approaches, as when these approaches fail, distressing feelings for the practitioners can be attributed to structural and systems failings (Ruch, 2012). The reality is that all approaches will, at times, fail as we are dealing with human beings who are shaped by conscious and unconscious forces, socially and culturally constructed, and thus each is unique. What worked in the past may fail for the present child or young person. We would do better, in my opinion, to accept that failure is always a possibility and to seek solutions from whatever discipline, theory or approach that may best meet the needs of the individual child or young person. If we then fail, we can only learn from this and accept that this failure and the attendant distressing feelings, is part of our challenge in caring for traumatised and vulnerable children and young people.

I have known failure in my time in residential care within which I played a causal role in and I must accept that had I acted differently, in ways that hindsight now reveals would have been more appropriate, then this failure may have been averted. However, hindsight only comes after the event, ostensibly too late to be of use in our current practice yet the potential that hindsight affords is not unrealisable to us in our current practice. We can learn from it via processes of (critical) reflection and thus it can reveal how future events may unfold if we apply past actions (foresight). This can then reveal insight into both ourselves and the consequences of our actions on those we seek to assist. Knowing ourselves and knowing the children and young people in our care, are two of the most important factors in social care. Each worker is themselves their most protective and empowering factor they can utilise in their work supporting children.

Whether induced by advancing age – a consolation of which is a growing body of accrued experience affording plentiful opportunities for hindsight – or a coping mechanism to deal with the failures inherent in caring for traumatised children or possibly vainglorious delusions of academic/intellectual grandeur – I find myself increasingly engaging in the pursuit of attempting to turn hindsight into foresight to reveal insight. Whatever the motivation, the results validate the process.

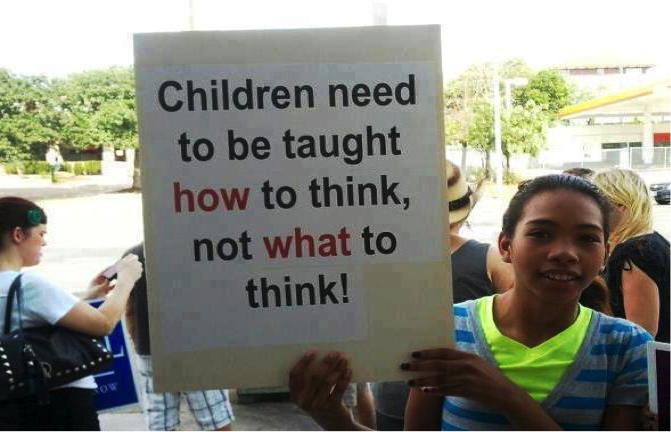

I have shifted position on these aforementioned continuums many times over my career and I have no doubt I will continue to do so in years to come. In fact, I actively seek out this change as for the past 16 years I have been continuously involved as a student in third-level education of which I find one of the greatest attributes to be this evolution of perspective which results from the gradual development of the understanding of how to think critically. Each child is unique, and so their needs will be best met at unique and shifting locations along these continuums and therefore we must be prepared to shift along these continuums with them.

My life experience to date, including being a parent, coupled with my professional experience and education, has caused me to come to the belief that the one truth that this experience and education can be distilled into is simply to try to do the right thing in any given situation. There is no need to enter into academic debates on ontology, epistemology or ethics to determine what the right thing is, as although they are important issues, and indeed relevant to this topic, a deeper understanding of their meaning and implications is not essential to address this issue. This is a question of right and wrong and one all parents strive to teach their children and all parents do not have a deep knowledge of these complex concepts yet most do a ‘good enough’ job of imparting the distinction to their children.

For practitioners in social care, there are many factors influencing us in our practice. These include what is expected of us by ourselves, our colleagues, our employers, and for some of us, employees, the children and young people, their families and our families, our training and professional code of ethics, society, insurers, our careers and inappropriately imposed imperatives of financial self-regulation that have been introduced in recent decades via neo-liberal hegemonies and then compounded by remorseless austerity, that the one constant within this melee, superseding all others, is to try to do the right thing. We need to strive to do this regardless of the potential personal consequences, whilst being mindful of unintended consequences for all parties concerned. However, it is important to recognise that unintended consequences can be both good and bad so we cannot become paralysed into inaction for fear of invoking possible negative consequences – as Ulrich Beck describes with reference to what he calls ‘bads’ in today’s risk society.

Experience and education can enhance our insight into unintended consequences but the right thing is an overarching immutable, yet dynamic, construct. Fixed, in as much as once it is identified it cannot be redrawn by rationalisation for our benefit but dynamic in that it is influenced by many factors which engender cultural and socio-economic contextual dimensions to this construct. A seemingly simple, values-based rather than a formulaically-derived concept, but, in my experience far from simple to identify and implement, requiring constant self-reflection and vigilance with an acceptance that sometimes we have to learn through our failures. Our failures can, sometimes, afford us insight into our failings.

After many years of striving to do things right, both as a worker and later as a manager, but increasingly becoming aware that sometimes what I was doing – albeit I was doing the correct thing ‘by the book’ and adhering to my training, the policy, procedures and protocol manuals, and achieving targets identified by external authorities – was not necessarily always in the genuine best interests of the children. Care has become increasingly bureaucratic in the past two decades, incrementally distancing itself from authenticity and all the while complicating the natural in pursuit of risk minimisation and elimination, ostensibly for the child’s protection. Risk is predominately perceived as a negative construct which favours managerial and bureaucratic approaches (and insurance companies) but without due consideration for the positive dimension of risk for children’s development. For example, increasingly over this time, I found myself having to tell a child in care that they could not undertake a particular activity as it was deemed too risky by some policy or other whereas I would readily let my own children do the same activity. Whilst I recognise that children in care may have some different needs than my own children I also recognise that they have a right to as normal a life as is possible to afford them whilst their needs are being met. In an era where targets and indicators are increasingly becoming commonplace within social care management, I have come to believe that to try to do the right thing must be the target for the social care professional – the most righteous key-performance indicator.

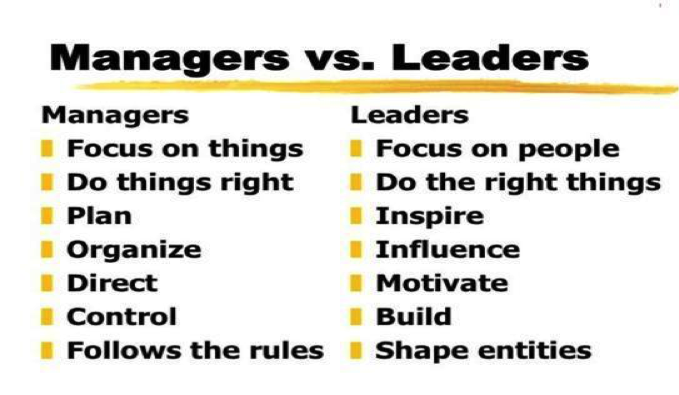

I came to see, largely through processes of critical reflection, that doing things right is a very different thing to doing the right thing with the former being the less-risky and simpler route, often with short-term aims and external locus-of-control processes for both worker and child, whilst the latter is risk-laden and complex but with longer-term change potential achieved via internal locus-of-control processes. This caused me to query just what we are trying to achieve in residential care and, on a wider scale, the primary task of the social professions. If the goal is to keep the children safe within a statutory framework then the protection and behavioural approach will likely be dominant though I sometimes query who or what is being most ‘protected’ by these approaches? Is it the child or is it the agency, company and/or professional? Whereas, if the goal is to aid children to reach their full potential then humanistic, risk-tolerant and relational approaches will likely be the most appropriate. If the aim is both, as it is for Tusla (the statutory Child and Family Agency which was established in January 2014), then it is imperative to guard against either approach becoming dominant and to this end leaders, rather than the predominance of managers, so evident in the former HSE structures, will be critical for Tusla. True leaders, who can also be managers, grow more leaders. These leaders will be critical to achieving the essential cultural change from that which was formerly in place within the HSE.

Education and experiential learning play a major role in these processes both for children and workers. With the focus of secondary and tertiary education, with social care courses no exception, on quantifiable and measurable standardisation including techno-rationally defined outcomes heavily dependent on rote-learning, and learning outcomes that are informed by statutory authorities and employers, the deck is stacked towards the protectionist position. Yet we extol the place of critical reflection within social care practice without developing the required skills of critical thinking in our students. I believe that the following holds true not just for children but for young people and adults also:

The correct thing to do is not always the right thing to do and it is also a truism that that just because we know the right thing to do does not necessarily mean we will actually do it. In the transactional processes of employment, we exchange our time, energy and commitment to our employer and our profession but not our integrity.

Social care with children and young people, in my opinion, is best served by appropriately promoting relational approaches with recognition for practice wisdom within values-based and outcomes and evidence-informed services rather than outcomes-based or evidence-based services. To this end, we must address the issue of the values underpinning our practice and profession and query whether what we find is compatible with the values of the social care profession we aspire to and then take action on our findings. Professional activism is our professional responsibility.

Leaving Care

Granting a right to an assessment of needs for aftercare support via the development of an aftercare plan which the proposed legislative change to aftercare provision, The Aftercare Bill 2014, proposes to do, is a significant step in the right direction. However, this can also be seen to represent, whether intentional or not, yet another manoeuvre aimed at deferring and thereby avoiding taking the one essential step of granting statutory entitlement to a service for all care leavers. Currently, 40% of care leavers do not participate in work, education or training and thus are not the focus of the current National Leaving and Aftercare Policy (2011) which focus the proposed legislative amendment will not change. What this means is that, in reality, Ireland has a two-tiered aftercare service with winners and losers which I have addressed in the most recent edition of this journal, together with some of the multiple relationships framing social care – http://www.goodenoughcaring.com/the-journal/unity-through-relationship-2/ .

The use of language in social care is of profound significance (Hartman, 1991). This is evident in how we refer to, and therefore conceptualise, young people who must leave the care system. For many of these care leavers, it is the care that leaves them regardless of the ability to function without it, thus making the term care leavers misleading and in reality ‘care losers’ more accurate. The term care leavers infers that it is the young people who possess the agency in the leaving event and that therefore this is an organic or benign process. They do not, and it is far from an organic or benign event. For them, care is lost but their needs and vulnerability remain and are, in fact, multiplied and magnified by this loss of care. They must seek the essential resources, which formerly were available to them as ‘care’, to meet their essential needs which renders them ‘care seekers’ or ‘support seekers’. Aftercare, for these young people really means after care has gone posing the question – what and who is left after care is gone?

By promoting the principles of social justice we must then recognise that unaccompanied minors are also legitimate ‘care seekers’. They are first and foremost children and consequently are impacted by the same issues negatively affecting all children in today’s society as well as those issues negatively impacting children in care. However, for unaccompanied minors, these issues are magnified and multiplied as they live in a country not of their birth, which presents a host of challenges, and they are treated differently than all other children in Ireland. Then, on turning 18 they enter Direct Provision services and are potentially excluded from aftercare support. They too are legitimate ‘support seekers’.

In 2010, Minister Barry Andrews stated that the existing legislation, Section 45(4) of the Child Care Act 1991, was sufficiently robust and that, having been advised by the Attorney General, he was assured that it placed a statutory duty on the HSE to provide aftercare and that henceforth the HSE would do so. Norah Gibbons, then Director of Advocacy with Barnardos and current Chair of Tusla, gave the following response:

“It is simply astounding that the Government is writing off the very notion of a mandatory provision for aftercare. In the past year, we have seen numerous reports on cases of children whose young lives were cut short because of failings in the aftercare system; Government is refusing to learn the lessons of the past and continues to put vulnerable children’s lives at risk with an aftercare system that is inconsistent and under-resourced.” (Barnardos, 2010)

Unfortunately, but not surprisingly, Minister Andrews was wrong proving, if further proof was needed, that the only way to ensure that aftercare is provided to all care leavers is to compel the state to provide this with rights-based entitlement to an aftercare service for all care leavers.

“In some cases, no aftercare at all was provided to young persons who left the care of the HSE. This is a very serious cause for concern.” (Shannon & Gibbons, 2012, p. xvii)

Statutory entitlement to aftercare support is a means to, and guarantee of, actual comprehensive, coordinated and equitable change, rather than a conversation about change. This conversation about change has been ongoing in Ireland for 45 years now, having started with the Kennedy Report in 1970 and continued, largely unresolved, in numerous reports and inquiries ever since.

Given the fact that the four states neighbouring Ireland, Northern Ireland, Wales, England, and Scotland, have all placed aftercare on a statutory basis with progressive Scottish legislation, The Children and Young People Bill becoming active in 2015, it is difficult to understand just why The Republic of Ireland has not yet done so. Based on the experiences within these neighbouring states it is true to say that legislation alone is not the solution, however, it is also true to say that the solution is not possible without legislation. They would not all have introduced it otherwise.

Commendably, we have more care leavers now receiving a service than ever before and it is important to acknowledge that many care leavers currently achieve positive outcomes. Any examination of the deficiencies of our aftercare service should not detract from the remarkable achievements of those care leavers who overcome adversity and achieve positive outcomes. Nor should such a focus fail to acknowledge the dedication and commitment of many aftercare workers, social workers, residential social care workers and foster carers who go above and beyond the call of duty in attempting in very difficult circumstances to support care leavers. Rather it is the equitable development of the service and the promotion of better outcomes for all care leaves that is the focus of this examination. Consequently, the number of young people leaving care each year but who do not receive a service is essential data to inform any accurate evaluation of our aftercare service. It is a specious exercise to compare outcomes from this service favourably with outcomes from equitable rights-based aftercare services within neighbouring jurisdictions. In making such a claim, the results do not and cannot validate the process as, unlike the aforementioned pursuit of insight which is a cognitive process, here we are dealing with people’s lives and each must be afforded equal worth. To claim these outcomes compare favourably, and it must be said largely based on statistical data generated utilising suspect methodologies, is tantamount to claiming that the end justifies the means and as such contravenes the code of ethics of social care/work and is, therefore, unethical.

An alternative interpretation of such a comparison can, in reality, be seen to evidence that it is possible to achieve similar, if not better, outcomes in jurisdictions such as England or Northern Ireland, where there is an equitable rights-based aftercare service in operation, and yet remained within defined budgets. In 2013 the Trust’s in Northern Ireland Trust’s remain in contact with 98% of care leavers aged 19; 66% of 19-year-old care leavers were participating in work, education or training and of the care leavers the Trust’s were in regular contact with 69% were involved in work, education or training. In England, in the same year the percentage was 63% and in Wales 58% (DHSSPSNI, 2014:13).

Legislation provides robust protective factors by virtue of its equalising remit whilst also empowering workers, with attendant role- clarity and ring-fenced funding. Furthermore, legislation enhances corporate parenting which Mike Stein has defined as legal responsibility held by single within embedded, formalised, inter and intra-agency arrangements case-workers(Stein, 2012:9). Stein (ibid) also acknowledges the worker for their true value as the face of the corporate parent.

With regard to ring-fenced funding, it is of concern that the CEO of Tusla has identified ring-fenced funding of €16 million for aftercare services in 2015 when we had an expenditure of €17 million in 2012.

What Can Be

By doing the right thing for children in care and placing aftercare for all care leavers, regardless of their legal status, on a rights-based footing, Ireland, may finally become the ‘good enough’ corporate parent she aspires to be rather than the obdurate corporate parent she has been. This version of corporate parenting would be very different from what we have had to date. This would entail responsibility shared across all stakeholding agencies and government departments coupled with single case-holder legal responsibility thereby ensuring both the mandate to access resources with statutory authority and the continuity of relationships for all care leavers. We could be proud of such an aftercare service, an equitable, values-based and developmentally-appropriate service, with an expectation that all care leavers will thrive as opposed to some merely surviving – tragically and unconscionably, too many are currently not surviving the transition. This, for children in care, would truly turn the rhetoric of valuing and respecting each and every child in Ireland closer to becoming a reality.

We must learn the lessons from the past and do the right thing now and not wait for the plight of many care losers/seekers to become recognised at some future point in time as a case of further national shame where a grave injustice has been perpetrated against a forgotten, vulnerable and hidden section of Irish society.

We cannot rewrite history and erase the harm caused to so many care leavers in the past but we can right the wrong now.

References

Barnardos, (2010). http://www.barnardos.ie/media-centre/news/latest-news/children-cast-adrift-by-failure-in-aftercare-provision-barnardos.html

DHSSPSNI, (2013). http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/northern_ireland_care_leavers_aged_19_2012_13.pdf

Hartman, A. (1991). Words Create Worlds: Editorial, Social Work, 36, 4, 275-276.

Ruch, G. (2012). Where Have All the Feelings Gone? Developing Reflective and Relationship-Based Management in Child-Care Social Work, British Journal of Social Work, 42, 1315-1332.

Shannon, G. & Gibbons, N. (2012). Report of the Independent Child Death Review Group, Dublin, Government Publications.

http://www.dcya.gov.ie/documents/publications/Report_ICDRG.pdf

Stein, M. (2012). Young People Leaving Care: Supporting Pathways to Adulthood, London, Jessica Kingsley.

An earlier version of this article first appeared in the Spring 2015 issue of CÚRAM and also at http://www.goodenoughcaring.com/the-journal/doing-the-right-thing-for-children-in-care-and-support-seekers/